Minoans

Image licensed through Adobe Stock. Edited.

1976

[Photo] Some light penetrates the empty inner courtyard. Otherwise the neat grass is dark, and the shadowed lower edge of the flats almost disappears where the brick meets the ground. Meanwhile, fresh from Buffalo, I’m gazing out into what appears to be twilight. The auburn in my big curly beard is looking coppery. I'm on a balcony in St. John’s Wood at Jill’s mother’s flat in London, where three of Jill’s four sisters still live, and Jill and I are sleeping in her old room. Whatever might have been readable in my gaze or faint smile is hard to detect–our little disposable camera will never focus sharply on anything.

____

[Photo] Seaspeed the hovercraft has slid up onto the beach-like ramp of concrete on the other side of the Channel. A gray day. The huge black X’s of the four propellers are still as people move with their luggage out of the front of the ship, and in the frame they appear to be mainly the Greeks who take up ninety percent of the tour bus we share. Two Greek drivers. Two Australian couriers, bigots, disdainful of Greeks. Already the drivers and the couriers are feuding, and eventually, somewhere in Yugoslavia, they will actually fight, with punches and kicking. A little later, in the middle of the night, the bus will stop on a deserted street in some small Yugoslavian town and the drivers will threaten to dump out all the non-Greeks, which all the non-Greeks believe. The next day, as soon as our bus crosses the border, all the Greeks break into song and don’t stop until we arrive in Athens, hours later.

____

Like pewter in their color under a cloudy sky, like mercury in the cool molten way they split and unfurl, Aegean waves at the prow of the Lemnos are cutting away and falling back toward Piraeus. Staring over the rail, I’m fretting that my wire-rims might drop off and be lost in these ponderous waters among rhyta, settle with bones of the ancient drowned, as I try to but can’t remember the Greek for “wine-dark.” The sea wind is cold and exciting and I want to be with Jill on the upper deck chatting with Marie (in hip peasant garb, lead beads from Afghanistan, French) or those rich American undergraduates from Philadelphia–Jill smoking Ethnos, head back, her red-blonde hair long and trailing, the rosy profile of a Celtic warrior sharp in the damp buffeting air on this overcast day. And she’s laughing, I imagine, her hearty laugh.

____

Our cab winds up a narrow curling road transformed by the night and headlights into a tunnel lined with gray scrub, gray stunted trees, a monochromatic world flaring up out of general blackness unrelieved by any light of house or sign and then shrinking back to annihilating dark. The Greek cabdriver affirms what Marie is saying about vampires, legends of vampires on this island, centuries older than Stoker and Nosferatu and Vlad, while the dashboard glows like a comforting little hearth when everyone in the cab falls into an eerie silence that rides with us up the crown of Santorini. And when later we twist down sloping volcanic cliffsides of pumice and red and black basalt it goes there too—it is good to be traveling the narrow road from Fira on the terraced outer edge of a blasted-out caldera, on an island like a tattered crescent moon. This is a good way to ride into a place I’ve never been, knowing a little of how it used to be here. The dank night air floods the cab and I’m thinking about what was lost and buried with Akrotiri, or buried under the sea, in lava.

____

There was little left behind, no jewels, no bones after the people fled because the earth was jolting again and again. Squatters and those who sought plunder moved into the outskirts of abandoned cities, and when the eight-mile vent of volcano rips open finally they suffocate and incinerate, die in seconds when some fifty cubic miles of rock and everything else from what seems to be a pleasant realm–one “Minoan” heartland–ascends in 1628 BCE. The light of the blast is Hiroshima-like as the pyroclastic superheated chaotic currents of toxic gas swirl inside a wall of ash rolling like a tide, carbonizing everything organic.

Granite walls and flagging, cultivated fields and aqueducts and gracile blue monkeys, amorous split-tailed swallows, elegant antelope of the murals, elegant barques, walls threaded with ceramic pipes for the cold water and the hot thermal water, rivers of fresh water and everything beautiful, everything otherwise, everything to the depth of a mile ascends in fragments, blasted, incinerated, shattered and rising at twice the speed of sound.

A tsunami roars up. Along at least one riverine shore the wave pulses eight hundred feet high.

A thalassocracy gone. Shrine of the Lilies, Shrine of the Ladies, buried. Imagine being in a trireme, looking back at a moment audible in Asia, visible from the moon.

A shepherd somewhere distant, head inclining, cups an ear. The flock goes still.

____

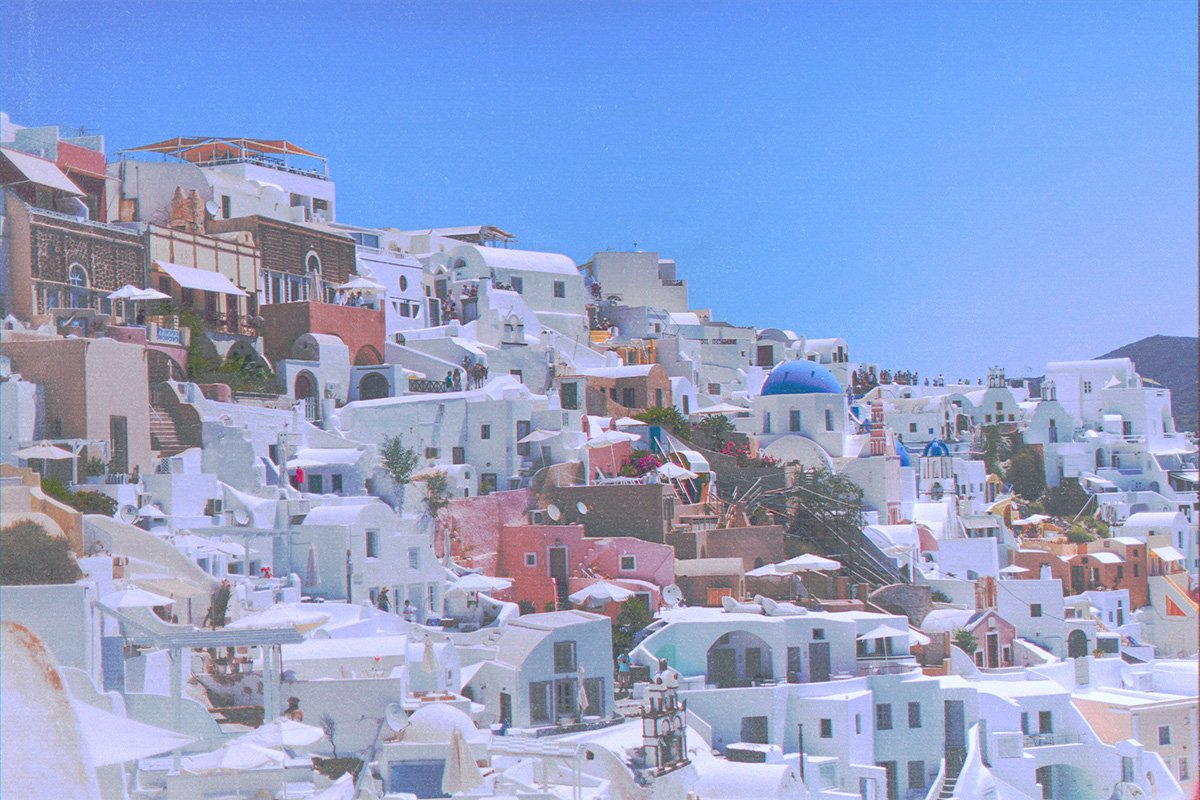

[Photo] West of our balcony in the Hotel Fregada, the bleak dark caldera, the Burnt Islands. Active fumaroles, sulfide vents, bacterial oases. This pleasant hotel is owned by Marinos Passaris, Marie’s friend, apparently a boyfriend. She recommended Oia, this hotel. It’s new. No one else is here in the off-season except Marinos and Marie, and Jill and I who have a room at the end of the main hall, and a balcony. We can stare down the steep arid western slope of Santorini past the stunted ground cover and purple shade of midday into the famously blue water, never numb to it. Out there on sunny ripples a lake might make, one fishing boat, a fingernail sliver, bobs.

____

[Photo] Down spines of ridges scoured and pocked like weathered bones, the houses of Oia flow white and curvilinear. They look extruded among the spring daisies and coastal succulents. The sky is pale. Two people far away stroll by a white wall, a doorway painted teal. Uncluttered telephone poles recede. Slow afternoons. Goat’s milk yogurt and feta, olives, tomatoes, fresh bread we eat in our room, retsina, dark local wine. No dope–we chickened out. Blur of skin, kisses, fucking, sleep.

____

As remote in its way as news from the dead ruined palace of Knossos, some news in English crackles from a transistor radio by a bowl of sprouted lentils six inches tall. The news is from Heraklion, the US Armed Forces Network: someone named Carter “wins big” in Pennsylvania, where Reagan whips Ford and Hubert won’t run. Twelve varieties of snails are now in danger. A solar eclipse will occur on the 29th. The DJ, on Easter, “will respectfully play subdued music till midnight” and no TV will play at all here, with none around, which fits our mood–like the radio off. In a moonlit patch beside the bed, a lizard pauses between steps, one tiny delicate foot suspended mid-air.

____

Aegean light is glowing on low buildings whitewashed with marble dust in a slurry of paint in the village of Oia. Down the cobbled street, glad to see us, trots Iatis the dog, a lanky piebald hound with a gait more like prancing than anything else, as if–I think later–proud of what dangles from his teeth and clatters now and then on the stones of the street like a plastic baseball, a prize says the way he approaches, and then finally you see what bounces at the end of what looked like a cord or piece of rope: the skull of a house cat, its two prominent canines like a vampire's.

And here comes “Captain Dracula,” in fact, out for a stroll in his nautical regalia, passing by a hand-painted sign listing all the products of Santorini, a.k.a. Thera, meaning "Fear" (or "Monster"?), once Kalliste, Most Beautiful:

WINES

TOMATO PASTE

PISTACHIOS

SPLIT PEAS (FAVA)

CARPETS

HANDICRAFT

PUMICE STONE

VOLCANIC ASH

His real name is Dacaronis, distinguished gray beard, really a captain who sails the Aegean. He smiles at Jill and me, who stand near the public clock stuck at 6:10. The man is elegant and affable. Everyone seems to know him. Everyone in Oia calls him “Captain Dracula.”

____

Every horizontal wire overhead throbs in early Etesian wind, and together they send out a humming cry like a torrent of souls. The whole sky is loud. At night the effect is even more impressive, and tonight the people, the villagers and visitors, celebrate Easter with relatives and friends. People gather near the church at night and talk and stop and look up at the stars while the windy night sky goes on moaning like an endless lamentation of the damned.

____

I cook fish all day on the day before Easter, small fish, in oil. I cook them till their eyes bug out and collapse and flatten, then I give them to someone who serves them in the restaurant section of the Hotel Fregada. Or I wash dishes, forced to be careful with the water hauled in expensively by tankers. Two men sit and play violin and bouzouki all day, 100 drachmas a dance, and Marinos gets pissed-off about glassware thrown down and broken on his new and beautiful floor of polished marble chips. Jill works too, we work to help out Marinos who squabbled over something with his mother and aunt and so lost both for the day, disastrous.

From noon to midnight the revelers come and go and dance and eat and drink. The portly wife of a local Greek–"She’s a Nazi,” says Marie–dances with her smaller husband, somehow confirming what people say, that the Germans marry here to take over, opening boutiques, fetching exorbitant prices for “Handgemachten Sandalen,” promoting summer in “OIA-VILLAGE” with brochures (“Griechischer Inseltraum”) hyping recreation by the “tiefblaue see: Wandern...schnorcheln...Grillparty machen...” usw.

When the customers leave at last and the staff that worked hard all day settles down with leftovers, I gnaw on a big hard hunk of mutton pried from the roasting pan, hungry, rolling the piece in my slick hands for another bite, halting above an eye, large, glazed, staring back.

____

[Photo] On the eastern slope of Thera, on the outer edge of the crescent, long terraces march from one slope down to the next all the way to the sea. Vineyards thrive in the tuff in some, but here in no direction can you spot a tree or a house or much of anything alive except the daisies. Daisies fill all the land, millions, bright enough to make you think some of their light comes from below, shining up. Even here at a wall of basalt boulders the color of bloodsoaked mud, you think for a moment you might be able to kneel and brush aside a pad of aromatic chamomile and the dirt beneath and discover a brightness that ascends. But of course you don’t.

____

[Photo] Villagers can add rooms by digging out pumice and wiping down the walls with water, then whitewashing. On a slope to the right of our balcony, people had done that. Then one or more of many earthquakes here had broken up the houses, the homes. The land beneath broke and fell away and the people deserted these places to weather, to time. Clumps of rose-madder and daisies roped and draped and nested make the ruins more “picturesque.” The dark holes of what had once been rooms gape like caves, like old vaults long ago plundered, like tunnels from inside the island that run from its darkness to here, which is nowhere anymore.

____

Too far away for us to see clearly, someone in the inlet was diving for something by a beach of marble-laden sand, basalt, gray boulders of pumice everywhere in all sizes, regular, smooth, rolled by the surf into walls at a sheltering cliffside.

Otherwise we were alone on an afternoon meant to be fun—Aegean beach, water too chilly to swim but still exotic in its clarity and calm, like our depth of romance—while at this moment everything was faltering, changing in the light that shifted and died when the sun was eclipsed as we stood there, two webbed shadows glittering with tiny crescents when the new light altered our faces, as if to show in that amber cast how we were different together now, for the first time.

The strangeness frightened, like some doom quietly awakening under our feet, with no place to run to and no one else we wanted to go with but the one to escape from, the only one worth saving.

____

In her face was nothing distinctly male or female except her plump mouth. We had seen her now and then around Oia, always with a different pup. Running away to Athens, 17 or so, she huddles under a lifeboat on our ship back to Piraeus, a small dog hunkered near. She wears all she has—old tennis shoes, jeans, a big Army shirt. A large head of dark hair, curly. She could be a boyish girl or pretty boy. Only when she moves, shifting with the sun, is it clear from the deep slopes in the baggy shirt that she has large, heavy breasts. Sunlight there raises blood in me, musing in a deck chair, finding a story of the way I might turn to her, solicitous, genuine, offering help with no expectations. And then she grows to trust me, and then in exiting the weak shower one evening in the cheap but clean hotel room I’d rent and offer to share, she might cover herself with a towel, water cascading over slight black hair on unshaven calves, and because for our two or three days together I have been only kindness, only a brother, a friend (sleeping on the floor), she would halt for a moment, staring as the light catches those beautiful lips parting and then the towel drops etc., blah blah. I cross my legs, check my watch. Jill is reading Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick (in fact), and abruptly I resent not being alone, on my own. Suddenly I want a sybaritic misadventure, a shallow sexual interlude–knowing unpleasantly that I’ll remember this, already ashamed. Later we give the girl bread. She turns away and hunches over it, eating hurriedly, sharing with her dog.

____

[Photo] Marie has the camera. Our last day after two weeks at the Hotel Fregada. Putting sunglasses in the pocket of a denim jacket pulled taut by a small backpack, I look startled and morose–someone has intruded on a moment of inexplicable sadness, surely. A typical look. Wind fluffs my longish hair in front of the Hotel Fregada. Behind my raised indigo elbow, a blank severe wall, mottled gray as if partly erased. Above the wall stands a gnarled, leafless tree, the top of which just reaches the top of the totally planar house it fronts. The door of the house is green, the walls tan and white, colors scumbled. A single telephone line angles down across the frame. Two tattered clumps of daisies cling to a nearby wall of white rubble, some old foundation. The sky overcast, everything subdued by it.

____

[Photo] Now our luggage sits to our right, a canvas bag, gray suitcase, that heavy red one. Jill and I stand in the center of the picture by a waist-high wall at the side of the Hotel Fregada. A thin bluish pipe rises out of a corner of the wall and curves over at eight feet or so, ready for the canopy that shades diners in the warmer months to come. The old foundation next door is piled behind us. We stand with our denim-clad bodies pressed together, side to side, my arm curling over her shoulder. Her hair is wrapped and hidden under a long purple scarf. We look embarrassed in exactly the same way, our eyes cast down, both sheep-faced. Only Iatis the hound, head poked into frame, faces the camera. His eyes are completely in shadow.

____

Through a window in the grimy train bound for Gatwick, I squint to see Jill raising an arm in a wave, holding it there as she stands on the platform at Victoria Station. Travelers hustle all around her. Metal scrapes metal, steel groans when the train to Gatwick slowly begins to roll. In her large pale eyes, as she recedes, I think I see something like anger—probably—and turn away to wipe and adjust my wire-rims. I run my tongue along the orange bristles of my mustache, salty. The train leaves the darkness of the great shed, plumes of smoke, Jill is gone and I'm going toward the darkness of the next tunnel ahead. Small clouds from a gray sky full of clouds seem to be dropping down on the train, as if everything wants to mean something dramatic, and I sit there not knowing what.

Dan Howell’s collection of poems, Lost Country (University of Massachusetts Press, 1993), was runner-up for the Norma Farber First Book Award of the Poetry Society of America and shortlisted for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in poetry. He received a citation for Notable Essay (“Cowards”) in Best American Essays 1993. He is the author of a chapbook of poems, Whatever Light Used to Be (Workhorse, 2018), and a book-length narrative poem, Eden Incarnadine, or The Authentic History of the Terrible Harpes (Broadstone Books, 2019). He lives in Lexington, Kentucky.